Darius Dhlomo:

A Footballer in the Era of Apartheid

Excerpt from "Darius Dhlomo: A Footballer in the Era of Apartheid" by Peter Alegi published in Africa e Mediterraneo n. 71, "Storia e pratiche del football in Africa"

This biographical study of Darius Dhlomo1 begins to uncover the sporting past of a transnational and iconoclastic South African footballer and deepens our understanding of broader processes of change in South African football between the 1940s and the1960s. In striking, even surprising ways Dhlomo’s career brings to life key aspects of South African football’s transformation from a local racially segregated amateur game to an increasingly mixed semi-professional sport linked to trends such as international tours and labour migration. Based primarily on two lengthy interviews with Dhlomo by the author, as well as archival documents, articles from the black press, and secondary sources, this biographical study of Dhlomo attempts to shed light on the extraordinary (yet largely hidden) sporting past of a transnational, polyglot South African iconoclast.

Childhood and youth2

Dhlomo was born in 1931 in the port city of Durban – the major outlet for the Witwatersrand’s mining and manufacturing industries.3 He grew up in Baumannville, the city’s oldest African township, located on the site of today’s central railway station. Opened in 1916, it was a relatively privileged neighbourhood with many stable families – very unusual in a city where nearly 70 per cent of Africans were single male migrants working low-wage manual jobs. The Dhlomos were a Zulu speaking Christian, aspirant middle-class family. They worked extremely hard to pay for their children’s mission schooling in the firm belief that Western education was the key to upward mobility. The Dhlomos’ strategy was vindicated by their children’s success in gaining access to the only “professions” Africans could aspire to due to the “job color bar”:4 teaching, nursing and preaching.

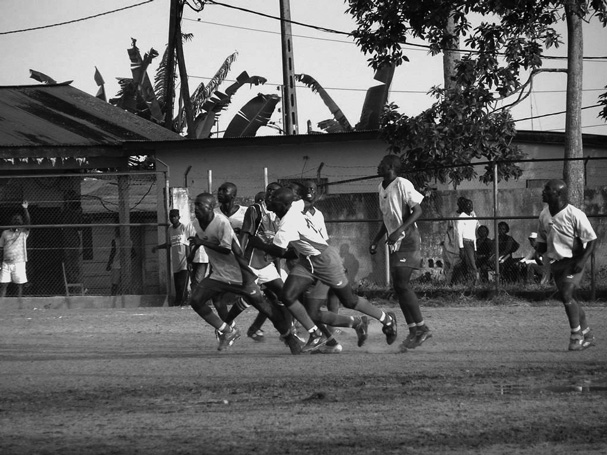

In Baumannville, as elsewhere in colonial urban Africa, intense football games in dusty streets, sandlots and schools shaped the everyday lives of boys. «We started playing soccer because our parents couldn’t afford buying shoes, football boots», Dhlomo told me; «so we started playing on the streets in the location barefooted. [It] was one of the sports we could do without having to pay any money!»5 As a teenager, Dhlomo liked to play goalkeeper. He did so with characteristic zeal, and in 1946 he joined Baumannville City Blacks.

Founded around 1939, City Blacks gained the eager affection of Baumannville’s residents and quickly emerged as a contender in Durban football.

In 1947, at the precocious age of 16, Dhlomo’s talent, fortitude and discipline between the goalposts earned him selection in Natal’s representative team for the Moroka-Baloyi Cup – the most prestigious national football tournament for Africans.6

Football was neither Darius Dhlomo’s only passion nor his only forte. He developed into a menacing boxer. Nearly six feet tall and weighing about 160 pounds, Dhlomo won the black national cruiserweight title (a category for men up to 40 pounds heavier than he), as well as the Natal middleweight title in the mid-1950s.7 Regrettably, the Boxing and Wrestling Control Act of 1954 prohibited inter-racial professional boxing matches (and sparring) so Dhlomo never fought against white boxers in South Africa.

Alongside football and boxing, Dhlomo cultivated a visceral love of music – particularly American jazz.8 «Duke Ellington and Count Basie and Nat King Cole: these were the models for us».9 Gramophones in the townships blasted recordings of Louis Armstrong and other American greats at weekend parties. Hollywood films heavily influenced black urban entertainment and sociability in Durban and elsewhere in colonial Africa.10 Hollywood films inspired Dhlomo and friends to form a vocal quartet. Music, like sport, carved out unusual possibilities for black self-improvement, raising self-esteem and acquiring social honour in a racist and appallingly unequal society.

«When I was still a young boy, eh, in the period of Apartheid, we had no other choice but to be creative», Dhlomo remarked. «And to be creative we pulled ourselves up, from the situation at the time of the Black American (…) The best way to survive is do something!»11 That Darius Dhlomo came of age in the 1940s seems crucial. Fluidity, turbulence and uncertainty defined this important decade in South African history. «In no sense, other than the minds of its adherents, was the advent of Apartheid [in 1948] preordained», historians Saul Dubow and Alan Jeeves noted recently.12 The main reason for this flux was the Second World War.

The massive intensification of urbanization and the Allies’ need for strategic and economic assistance led the South African government and the private sector to make some economic and social reforms. Most notably, «they eased the job colour bar, extended the industrial training facilities for Africans, raised black factory wages by a larger proportion than white wages, made Africans eligible for small old age and disability pensions, and increased the grant for African education and freed it from its dependence on African taxes. In 1942, they even relaxed the pass laws».13 For reasons that are beyond the scope of this essay, this reformist moment turned out to be “short and exceptional”, and by the time the Afrikaner National Party came to power in 1948 on a platform of Apartheid (“separateness” in Afrikaans), «the window of opportunity had closed».14

Maturity

As the white regime quickly enacted the legislative pillars of Apartheid, Dhlomo passed the high school matriculation (“matric”, or exit) examination. He weighed his options and, after completing his teaching training, took a teaching position at Lamontville High School.

The harsh and hostile environment of Apartheid education made teaching in black schools an enormous challenge, even for committed instructors like Dhlomo. «At the time every teacher had to give seven subjects. I taught geography of the world, history of the world, music, geography, physiology and hygiene, Zulu language», Dhlomo said.15 After school, Dhlomo went to football training or the gym. […]

Peter Alegi is an Associate Professor at Michigan State University, teaching courses in African history, South African history, and global sport. He is the author of African Soccerscapes: How a Continent Changed the World’s Game (2010) and Laduma! Soccer, Politics, and Society in South Africa (2004), and has published many journal articles and chapters in scholarly collections. He is an editorial board member of the International Journal of African Historical Studies and book review editor of Soccer and Society. With Peter Limb, he co-hosts Africa Past and Present – a widely accessed podcast about African history, culture, and politics, and has appeared on BBC World Service, NPR, Radio France International, Radio Democracy, and SABC (Motsweding). He is currently a Fulbright Scholar at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa

Notes

1 – I would like to thank Jill Kelly for transcribing interviews and Chris Bolsmann for providing several images and helpful comments on earlier drafts of the essay. All interpretations are mine.

2 – This and other sub-headings are borrowed from Van Onselen, The Seed is Mine.

3 – This biographical information on Dhlomo comes mainly from two telephone interviews with the author on 12th February and 25th February 2003.

4 – Racial discrimination in employment was first legislated by the South African parliament in the Mines and Works Act of 1911 (revised in 1926), which excluded Africans from skilled (and better paid) labour in the mines. The Industrial Conciliation Act of 1924 extended the “job color bar” to other sectors of the economy (and also made African trade unions illegal).

5 – Interview with Dhlomo, 12th February 2003.

6 - For more details on the racially balkanized structure of South African football, see the introduction to this volume and Alegi, Laduma!

7 – Dhlomo was able to fight above his weight due to the lack of contenders in the heavyweight and cruiserweight categories in black South African boxing in the 1950s; see Fleming, Marvelous Muscles, p. 15. A scholarly history of black boxing in South Africa has yet to be written.

8 - On the connections between black American music and black South African music see, among others, Coplan, In Township Tonight!; Erlmann, Black Stars; and Masekela and Cheers, Still Grazing.

9 – Interview with Dhlomo, 12th February 2003.

10 – Ambler, Popular Films and Colonial Audiences; Davis, In Darkest Hollywood.

11 – Interview with Dhlomo, 12th February 2003.

12 – Dubow and Jeeves, South Africa’s 1940s, p. 2.

13 – Thompson, History of South Africa, p. 181.

14 – Seekings, Visions, Hopes & Views, p. 61.

15 – Interview with Dhlomo, 12th February 2003.